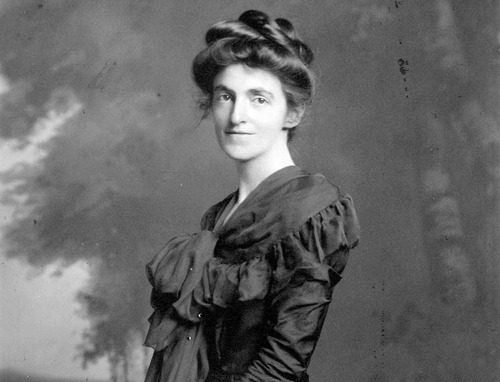

Sophonisba Breckinridge was a prominent supporter of women’s suffrage and a pioneering social work activist. She was also the first woman admitted to the Kentucky Bar. Sophonisba was actively involved in several key reform initiatives throughout her life, laying the groundwork for future generations to improve their working and living conditions, as reported by chicagoka.com.

Childhood and youth years

Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge was born on April 1, 1866, in Lexington, Kentucky. She was the second child of Issa and William Breckinridge. The girl’s father was a congressman and a well-known lawyer, while her great-grandfather, John, was a Kentucky senator and attorney general under Thomas Jefferson.

In 1888, Sophonisba graduated from Wellesley College for women, after which she began a career as a teacher in a Washington school. She then spent a year in Europe before returning home to practice law in her father’s office. Although the man was adamantly opposed, the daughter insisted on her choice. In 1894, she became the first woman admitted to the Kentucky bar.

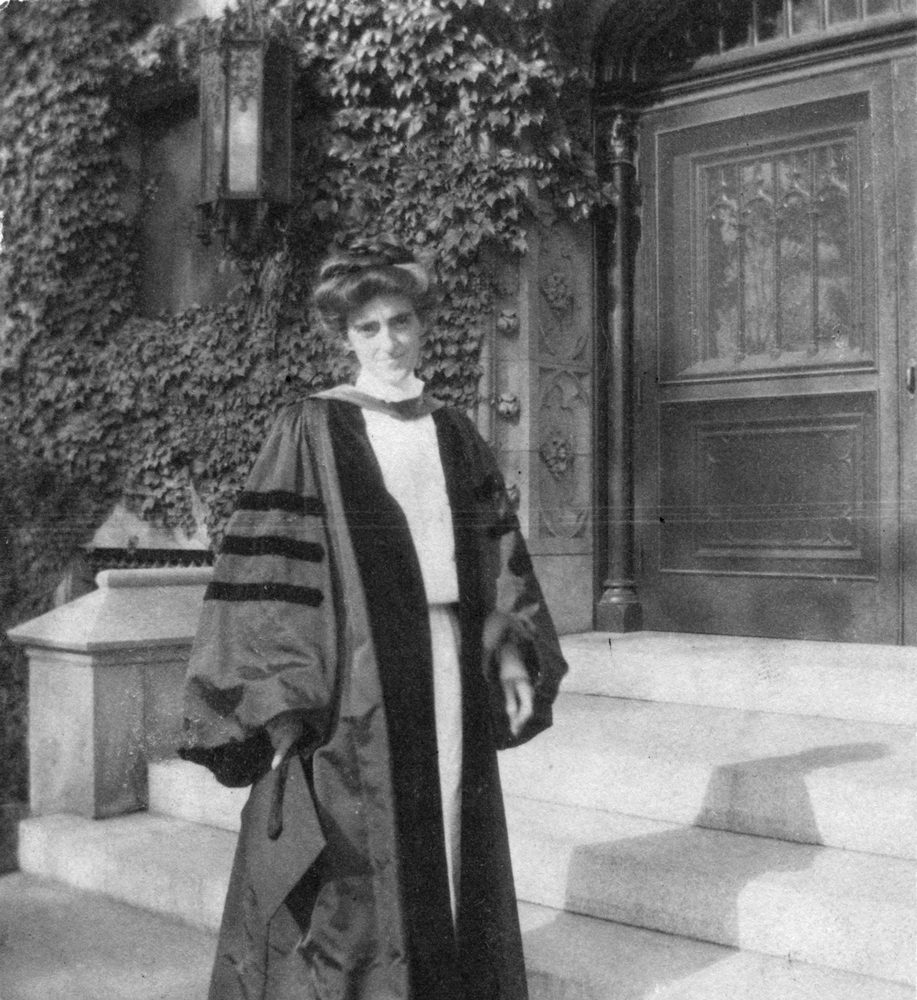

In the late 1890s, Breckinridge made the decision to relocate to Oak Park, Illinois, and enrolled in the University of Chicago’s doctoral program. In 1901, she became the first woman to receive a doctorate in political science from the University of Chicago, and she graduated from its Law School in 1904.

In 1906, Sophonisba met Edith Abbott and concentrated her efforts on women’s labor and juvenile delinquency. In addition, she wrote for the American Journal of Sociology and taught at the Chicago Social Science Center for Training and Practical Training in Philanthropic and Social Work, which was later renamed the School of Civics and Philanthropy.

First research and activism

In 1907, Breckinridge joined the Hull House members. In the same year, she became a member of the Women’s Trade Union League and founded the Immigrant’s Protective League. In 1909, Sophonisba joined the University of Chicago’s newly established department of household administration as an assistant professor. 1909 also witnessed her first study under the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy on “The housing problem in Chicago”. During this time, she studied city policies and the practice of discarding rubbish in areas populated by immigrants and African Americans, which enabled her to uncover unsanitary conditions in Chicago’s working-class neighborhoods. Following the publication of Breckinridge’s work, the city modified its garbage collecting procedures.

Another significant research by Breckinridge and Abbott addressed the working conditions for women at Chicago meat processing plans. They spent four months inspecting enterprises and interviewed more than 2,000 female employees. As a result, they discovered terrible working conditions, low wages and unjustified layoffs. Breckinridge and her colleague Abbott immediately reported the study’s findings to the United States Labor Department, resulting in the establishment of the U.S. Children’s Bureau and the U.S. Women’s Bureau, which fought for the elimination of child labor and better working conditions for women respectively.

Breckinridge also pushed for the rights of African Americans by acknowledging the common occurrence of prejudice against women and black people, who she claimed were always viewed as members of groups rather than individuals. After joining the NAACP, she fought against racial segregation in Chicago schools and assisted in founding the Chicago Urban League, an African-American civil rights organization.

Breckinridge also participated in the women’s suffrage movement. In 1907, she co-founded the Equal Suffrage Association at the University of Chicago as well as the Committee for the Extension of Municipal Suffrage for Chicago Women. In 1911, she was named Vice President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In 1915, Breckinridge and Jane Addams co-founded the Woman’s Peace Party, which supported the federal suffrage amendment and opposed the war in Europe. Breckinridge later chaired the Committee on the Legal Status of Women from 1928 to 1930. During this period, Sophonisba successfully promoted the Cable Act, which helped to reform the legislation governing women’s citizenship rights after marrying immigrant men.

Academic activities

In 1925, Breckinridge became a full-time professor at the Graduate School of Social Service Administration, where she introduced innovative ways of teaching social workers. She then established the standard for social work education in the United States.

In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt appointed her as a delegate to the Pan-American Congress in Montevideo, making her the first woman to be given such honor. In 1934, Breckinridge was elected president of the American Association of Schools of Social Work.

Sophonisba recognized that social studies could serve to create a better society. Her legal education and academic background gave her a strong foundation for the work. She believed that scientific analysis had to be applied to solve practical and social issues.

One of this woman’s greatest accomplishments was her contribution to social work education. She started working as an assistant to Julia Lathrop in the School of Civics and quickly rose to the position of dean. However, due to insufficient funding, Breckinridge was compelled to negotiate the merger of the school with the University of Chicago. It is worth noting that this was the first graduate school of social work in the United States to become a branch of a major research institution.

Her other efforts in social reform included obtaining congressional approval for a national study of children and women wage earners, which resulted in the “Report on the Condition of Woman and Child Wage Earners in the United States”. The research highlighted the horrible working conditions in which women and children labored. The report helped to advance measures to improve women’s working conditions and abolish child labor.

Legacy

Sophonisba Breckinridge’s legacy includes being the first to be elected to various important posts, including the Kentucky Bar. By doing so, she paved the path for many other women to follow in her footsteps.

Her pioneering efforts in different social spheres resulted in numerous reforms, including the abolition of child labor, improved working conditions for women and the establishment of juvenile courts. Under her direction, new standards in the training of social workers were established and the University of Chicago rose to prominence as America’s social work center. Her belief that the state ought to play a more significant role in social security served as the foundation for the New Deal era.

In a way, Sophonisba’s career served as a vivid illustration of female activism in twentieth-century America. All of her initiatives were aimed at the same goal: establishing a fair and equal society for all. Her statements in support of people’s rights and well-being, research and publications that supported these movements, as well as promoting educational opportunities for women and teaching social work, changed the course of history.