The professional life of Chicagoans was and remains diverse. Many women were able to master professions that were previously considered male, writes chicagoka.com.

Early work culture in Chicago

Work culture is a set of ideologies and practices that arise during the interaction of people with the work environment. It was formed in Chicago due to the variety of employment opportunities. During the formation of the city, the fur trade culture actively developed based on the interaction between the Potawatomi and white traders. Marriages and customs led to the fact that many people began to adopt Indian traditions. Thus, in the early work culture of Chicago, there was a mixture of frontier autonomy of the indigenous culture, entrepreneurial values and financial independence.

Throughout the 19th century, work culture in the city was characterized by instability. Dependence on natural products for income – agriculture, livestock, ice and lumber – required people to act with the rhythms of the seasons. In spring, they planted vegetables and fruits. In fall, they harvested crops and collected wood. In winter, they cut ice, grazed cattle and pigs. However, no one was immune from drought or fires that could instantly destroy everything.

Common work in the 19th century

White men, as a rule, got temporary jobs. They obeyed a boss and worked during the season. Having received payment, they looked for another activity. For hard work, they were paid mere pennies, which was not enough to feed a large family.

Perhaps, the most popular activity in Chicago in the mid-19th century was the production of lumber. Lumberjacks from Lake Michigan hired workers, signing seasonal contracts with them. They had to work from dawn to dusk every day. Workers had to bring their own axes and pay for their transportation to the logging sites on the other side of the lake. As for the duties, the poor laborers had to haul logs, chop and stack them. In return, they received a room to stay, food and from $100 to $200 per year. Sometimes, their wives and children were hired to clean and cook.

In the early decades of the 19th century, the city had small workshops that needed craftsmen. Apprenticeship and subsequent employment were individual. Carpenters, plasterers, machinists and other tradesmen designed and manufactured products.

In the 1840s, the first canals and railroads appeared. Thus, by the 1850s, Chicago’s market had expanded from a few hundred miles to the entire country. The means of transporting people and goods over long distances had also appeared. Chicago became a hub for a wide range of goods: lumber, ore, pigs and cattle. After the Great Fire of 1871, the city saw a boom in construction, creating jobs for lumberjacks, carpenters, laborers and painters, as well as a need for stores and services.

The city’s particularly high demand for labor coincided with the influx of immigrants. In the 1850s and 1860s, Irish, German and Scandinavian immigrants arrived in Chicago. From the 1870s, immigrants from Europe began to come. All of them were looking for work and opportunities for advancement. These unskilled workers who did not speak English found jobs in factories, slaughterhouses and steel mills. By the 1890s, three out of four Chicagoans were either immigrants or their children.

Hard work for a penny

It is important to note that people came to Chicago not only from distant lands. Tens of thousands from small American towns and farms sought the prospects that opened up for them in the city. In the 1890s, many Americans arrived in Chicago from the South. Most black migrants were hired as servants and day laborers. In the 1910s, when industrial jobs opened up, African-Americans immediately joined them.

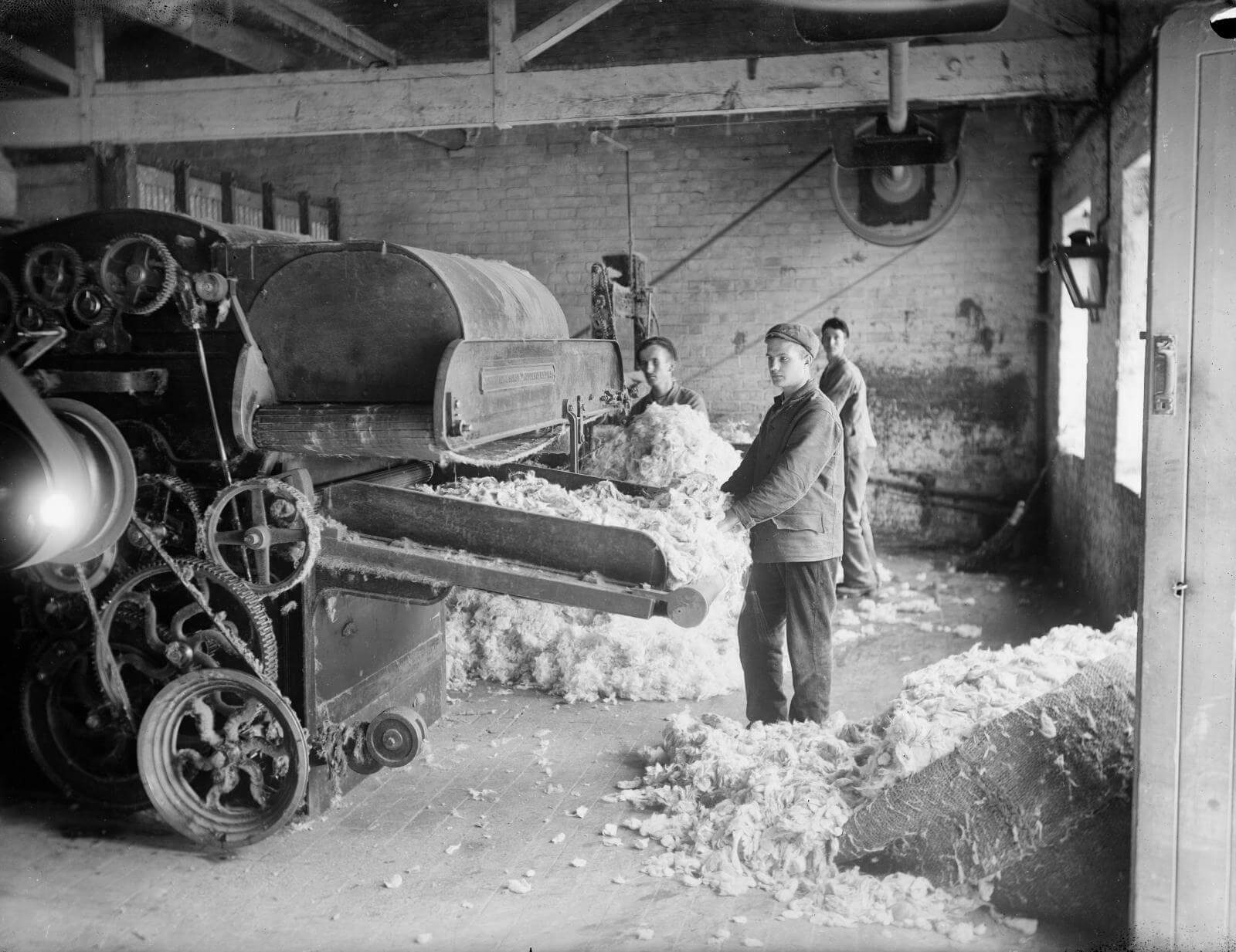

Factory workers were not specially trained and worked long hours in very difficult conditions. Most of them were white immigrants. Women preferred the garment industry. Factory workers made many products by hand for 10–14 hours, six days a week. By the end of the century, factories had grown into large enterprises. In 1800, over 75,000 Chicago workers worked in meatpacking plants, clothing factories, iron and steel mills, foundries and printing houses. By 1920, 70 percent of workers were employed in manufacturing. Personal relationships between employers and employees became more complex as businesses grew. The foreman of the factory supervised the workers, assigned hours and tasks and had the power to hire and fire. The methods of finding work were also noteworthy. People could find work through employment agencies, salons, labor unions and newspaper advertisements.

Prospects for women

In 19th-century Chicago, women were very few in the corporate world. They had fewer job choices than men. They were most often employed in garment, flour mill and shoe factories, as well as domestic servants and laundresses. Some turned to prostitution. Hilda Polachek, a Polish Jew whose family immigrated to Chicago in 1892, left school at age 14 and worked in a knitting factory on State Street. She operated a huge machine for 10 hours a day, six days a week, until she was fired for participating in a union meeting. Then, she worked in a shirt factory, sewing cuffs for 10 hours a day.

White indigenous women also found opportunities in new professions, such as vocational education and librarianship. They often found jobs as clerical and department store workers. Their wages were lower than those of men and unions were much less common.

In the 20th century, the professions that were defined as women’s had undergone enormous changes. For example, clerical work, which was once done by men, became women’s after the invention of the typewriter. As of 1920, the Chicago-based Montgomery Ward department store employed over 1,000 African-American women.

Domestic work, which had once included a group of workers who lived in the homes or businesses of their employers, became day labor. Women also worked as waitresses, despite the low pay.

In the second half of the 19th century, large department stores opened in Chicago, including Marshall Field’s, which employed many women. Managers taught saleswomen etiquette and merchandise. By 1904, the store had a staff of 10,000, serving up to a quarter of a million customers a day. The interaction between managers, saleswomen and buyers fostered social skills and initiative. It allowed retail workers a relatively autonomous work environment. Many of them were called women adrift, a term for unmarried women. They created a subculture of working girls in Chicago, challenging Victorian norms of behavior and influencing popular culture. This group of women, which included young, old, white and African-American, lived in boarding houses. They frequented restaurants, dance halls and theaters.

For most married women, the welfare of their families came first. They usually participated in public culture voluntarily and free of charge through churches, clubs and school societies such as the Parent Teacher Association. Thus, they contributed to the social environment. In addition, running a household and caring for children was also unpaid work. The husband’s salary was often not enough to support the family. Women supplemented the family budget by unofficially working as midwives, laundresses and selling goods at home.

In the 20th century, the culture of industrial work in Chicago began to change. Scientific management came to many large corporations. In this regard, modern production technologies started to be introduced in the shops. During this period, women began to work in factories that were previously inaccessible to them. With the adoption of certain laws, they gained access to numerous professions but that’s another story.